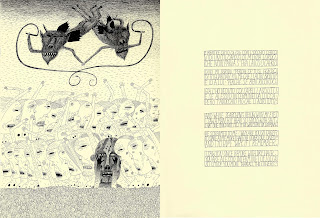

Inferno XXII: Ciampolo and the Malebranche

Ink on paper, 2016

22 x 15”

Their tour of the eighth circle continues in Canto XXII, and Dante and Virgil attempt to stall the brutal mauling of a sinner, plucked from the tarry pitch below, by asking questions about his background. While Virgil quizzes him, the antagonistic demons cut bits of flesh from the pitiful soul, but he ultimately escapes their escalating torture when he distracts them sufficiently—leaping from the cliffs to the black goo below. The scene is summed up at the end of the canto:

The

Navarrese chose his time well;

He

planted his feet on the ground, and in an instant

He

leapt and escaped their designs.

* * *

I remember having dreams as a kid in which I was hiding from something—a monster or some other menace (Blacula, or Charles Manson, glaring with his coal black eyes as he did in news photographs, were perennial threats). In these dreams I was always wedged in the triangle of space behind an open door, looking through the crack on the hinged side. While safe for the moment, the threat was imminent and I was terrified of being discovered, and then God-knows-what. The primal instinct to flee overpowered the rational need to remain in hiding and the decisive moment always came. As the perp came closer I would leap from my hiding place, arms and limbs flailing in self-defense, screaming like mad to scare him off. I would then find myself awake.

The last bit of Canto XXII of L'Inferno evoked immediately a now famous image from 9-11 known as The Falling Man. Having lingo ago reached meme status, I'm a little sheepish about my exploitation of it for this drawing, but it remains potent to me so I wanted to refer to it. The image is that of a man plummeting head first from the World Trade Center tower, his arms to his sides, his left leg elegantly crooked to lend graceful proportion. The beauty of the image belies its horrific narrative. Moments before, the man was on the ledge of the building, undoubtedly agonizing in the face of a terrifying decision: jump or suffer an excruciating death by incineration.

I like illustrating most when I am able to anticipate the visual literacy shared by most people and yet leave a few secrets to be discovered in the process of deciphering an image. Depending on this for dialogue with a viewer's memory and expecting their semiotic response system to engage, enabling them to answer the questions I am posing, can be deeply gratifying. This image unfolded that way, and—despite its tedious making—I really enjoyed all phases of its development.

I remember having dreams as a kid in which I was hiding from something—a monster or some other menace (Blacula, or Charles Manson, glaring with his coal black eyes as he did in news photographs, were perennial threats). In these dreams I was always wedged in the triangle of space behind an open door, looking through the crack on the hinged side. While safe for the moment, the threat was imminent and I was terrified of being discovered, and then God-knows-what. The primal instinct to flee overpowered the rational need to remain in hiding and the decisive moment always came. As the perp came closer I would leap from my hiding place, arms and limbs flailing in self-defense, screaming like mad to scare him off. I would then find myself awake.

The last bit of Canto XXII of L'Inferno evoked immediately a now famous image from 9-11 known as The Falling Man. Having lingo ago reached meme status, I'm a little sheepish about my exploitation of it for this drawing, but it remains potent to me so I wanted to refer to it. The image is that of a man plummeting head first from the World Trade Center tower, his arms to his sides, his left leg elegantly crooked to lend graceful proportion. The beauty of the image belies its horrific narrative. Moments before, the man was on the ledge of the building, undoubtedly agonizing in the face of a terrifying decision: jump or suffer an excruciating death by incineration.

I like illustrating most when I am able to anticipate the visual literacy shared by most people and yet leave a few secrets to be discovered in the process of deciphering an image. Depending on this for dialogue with a viewer's memory and expecting their semiotic response system to engage, enabling them to answer the questions I am posing, can be deeply gratifying. This image unfolded that way, and—despite its tedious making—I really enjoyed all phases of its development.